Representing Sequences

Before we get into actual data abstraction, let's first talk about the data structure we will use to store data: pairs. So far, the only way we know of storing information is to use sentences. In this section, we will introduce the idea of using pairs to combine and store data. Pairs are versatile and easy to build off of, for they can be nested within each other to create lists, data structures that are deceptively similar to the sentences from Lesson 1.

Pairs

In general, we as people tend to instinctively think of things as a collection or combination of multiple items. A book is a collection of words on paper. A salad is a combination of leaves and other yummy food. Now, let's shift this perspective. In Racket, and in much of computer science, things are represented by pairs. Now, how are we going to store multiple items if a pair is just two items? The second item of a pair, it turns out, is usually a pointer to another pair! And, if we have pairs point to other pairs which point to other pairs, we can store as much information as we want in this data structure. It adheres nicely to the rule in computer science that anything and everything can be represented in binary.

Creating Pairs

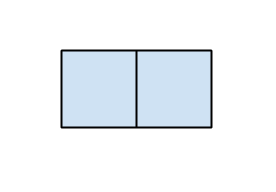

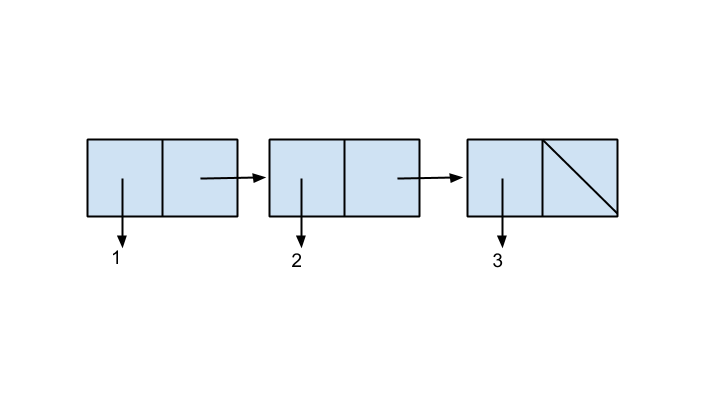

In Racket, we create a pair using the function cons, which takes into two arguments of any type and returns a pair. To represent this visually, we can think of a pair as a box with two halves:

The first half is called the car of the pair, while the second half is the cdr. They each have corresponding selectors of the same name. The procedures car and cdr both take in a pair as its only argument and returns the first and second item in that pair, respectively.

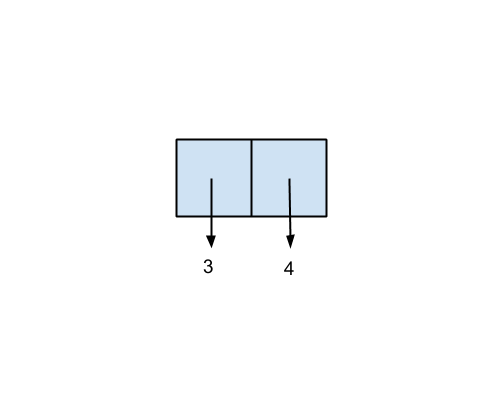

Let's take a look at the following example, where we create a pair of the numbers 3 and 4:

-> (cons 3 4)

(3 . 4) ;; notice how there is a period between 3 and 4

-> (car (cons 3 4))

3

-> (cdr (cons 3 4))

4

Visually, this pair would look like this:

This visual representation is called a box and pointer diagram, and is an extremely useful tool for understanding pairs when they get more complex in the future.

Let's see another example:

-> (cons 'hello 'world)

(hello . world)

-> (define greeting (cons 'hello 'world))

greeting ;; store the pair into a variable called greeting

-> (car greeting)

hello

-> (cdr greeting)

world

As you can see, pairs can store any kind of data - numbers, words, procedures, and even more pairs!

Write a procedure called func-pair that takes in a pair whose car is a function of one argument and whose cdr is a number. func-pair returns the value returned when we call that function to that number.

Try it out in the Racket interpreter first. Then, check your answers below.

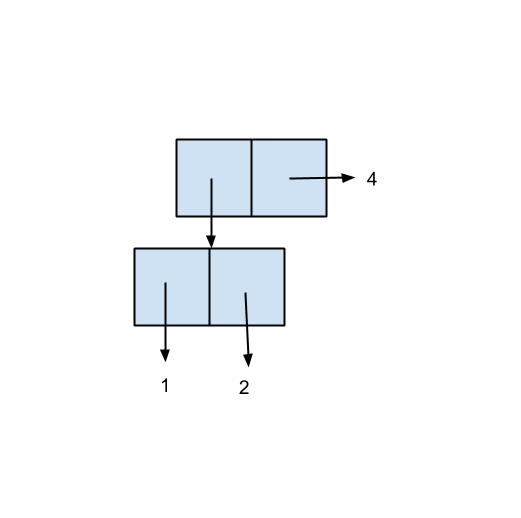

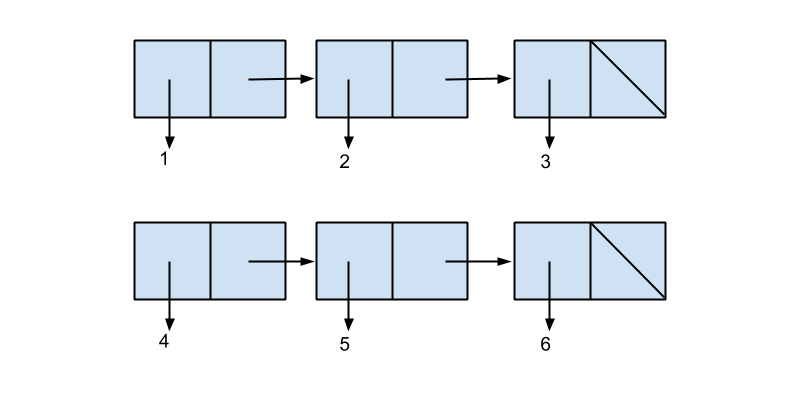

It's common for pairs to store other pairs, since this allows us to store as much information in one pair as we'd like. Let's see what the box and pointer diagram will look like for this nested pairs example:

-> (cons (cons 1 2) 4)

((1 . 2) . 4)

Notice how the car of this pair is another pair, (cons 1 2), while the cdr is 4. In that case, this should be how we draw the box and pointer diagram:

You can only imagine how many ways we can store large amounts of data!

Given the following piece of code:

(define z (cons (cons 1 2) 4))We can also have the cdr of a pair point to the empty list, which is written as '(). For example, we can do the following:

-> (cons 1 '())

(1)

Why is this useful? When would we ever want to store "nothing" into our pairs? Let's stay patient and look at the next example. Suppose we type this into the interpreter:

-> (cons 1 (cons 2 '()))

Try to draw the box and pointer diagram yourself, then try to guess what Racket would print out. Then, check your work with the interpreter.

Was the actual output what you expected? You probably assumed the expression would return something like (1 . (2 . ())). Instead, you got (1 2). This is because Racket has a nifty way of simplifying nested pairs! Since this format of (cons a (cons b (cons c (cons ...)))) is used so often, every time Racket sees a period followed by an open parenthesis, it will simplify the expression like so:

(1 . (2 . ()))

(1 2)Here are a few practice problems for you to try out. For each of the following expressions, try drawing the corresponding box and pointer diagram, then write out what the Racket interpreter will print:

(cons 4 5)

(cons (cons 2 (cons 4 5)) (cons 6 7))

(cons 3 (cons (cons 1 4) (cons 5 '())))

(cons 1 (cons 2 (cons 3 '())))

What will the following expressions return? If you get stuck, draw a box and pointer diagram.

(car (cons 4 5))

(car (cdr (car (cons (cons (cons 4 5) (cons 6 7)) (cons 1 (cons 2 3))))))

(cdr (cdr (cdr (cons 1 (cons 2 (cons 3 '()))))))

Some Shorthand

Series of cars and cdrs can be downright ugly. In our Racket interpreter, there is a built-in shorthand notation to do multiple calls to car and/or cdr.

(car (cdr a)) is equivalent to (cadr a).

(car (cdr (car (car a)))) is equivalent to (cadaar a).

Notice how in the first example, if we take the cadr of some sequence a, we first take the cdr of a, and then take the car of whatever is returned from that. In general, you can extract the a's and d's from a string of cars and cdrs, and append them together, in the same order, between one c and one r. You can do up to cxxxxr (4 x's), where x is either a or d.

Lists

Write an expression using cons so that Racket will print out (5 6 7 8). Click below to reveal the answer.

Using this pattern of conss over and over again can get pretty tedious. Because this is so common, Racket has another built-in procedure that creates a nested cons for us: list. list takes in any number of arguments of any type, and returns it as a nested cons, or a list. For example:

-> (cons 5 (cons 6 (cons 7 (cons 8 '()))))

(5 6 7 8)

-> (list 5 6 7 8) ;; this is identical to the expression above!

(5 6 7 8)

-> (list 'hello 'world 5 #t)

(hello world 5 #t)

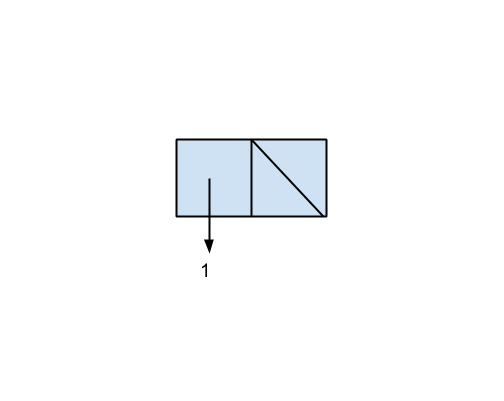

We can define list formally using the following recursive definition: a list is either the empty list, written '(), or a pair whose cdr is another list. Notice that this means that if we continuously take the cdr of any list, we will always end up with the empty list.

We can draw box and pointer diagrams for lists by simply rewriting every list as a nested cons. For example, the box and pointer diagram for (list 1 2 3) is the same as the one for (cons 1 (cons 2 (cons 3 '()))):

Thus, we learn a very important key idea: every list is a pair. The reverse is not true though - not all pairs are lists. (cons 1 2) is a pair, but it is not a list.

Append

We now have almost all of the tools we need to represent collections and sequences in Racket! What we’re missing is a way to easily combine two lists. For example, say we have the lists (list 1 2 3) and (list 4 5 6), and we want to combine these into one large list of the form (list 1 2 3 4 5 6). Racket has a procedure that does this for us: append. Given any number of lists, append will return one list containing all the elements of its argument lists.

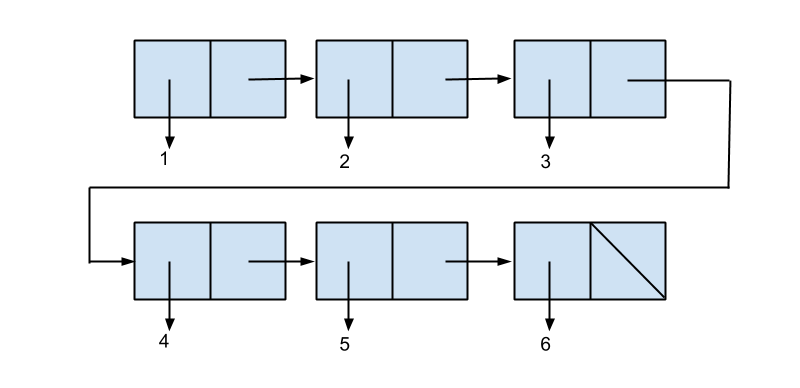

Here’s what calling append in the example above will look like with box and pointer diagrams.

We start with two lists, (1 2 3) and (4 5 6):

Then, we remove the null pointer at the end of the first list and point it to the beginning of the second list:

Append: Under the Hood

Here's how append works under the hood. Remember how our recursive definition of lists tells us that the last cdr of a list always points to the empty list? First, append takes its first argument list and follows the cdr pointers until it finds the last pair of the list. Then, it replaces the value that the cdr of that last pair points to with the second argument list to append. That might seem like a lot of nonsense to you. Take a look at the following example for some clarity:

-> (define list1 (list 1 2 3 4))

list1 ;; the last pair of list1 is (4 . ())

-> (define list2 (list 5 6 7 8))

list2 ;; the last pair of list2 is (8 . ())

-> (define list3 (list 9 10 11 12))

list3

-> (append list1 list2 list3) ;; we take the cdr of list1's last pair, which is the empty list '(), and point it to list2. then, we take the cdr of list2's last pair, which is also '(), and point it to list3.

(1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12)

Append will only work if all but the last argument are lists. Can you explain why the last argument does not have to be a list? What does Racket return when you call append where the last argument is not a list?

Which of the following calls to append will error?