Racket-1

Getting Started

Copy the source code for the Racket-1 interpreter into your current directory by typing the following into your terminal:

cp ~cs61as/lib/racket1.rkt .

Alternatively, you can download the code here.

To start Racket-1, type the following in Racket:

;; Load Racket-1 file

(require "racket1.rkt")

;; Start interpreter

(racket-1)

Familiarize yourself with Racket-1 by evaluating some expressions. Try typing regular Racket expressions and see what happens!

You might notice that you can't do everything in Racket-1 that you can do in normal Racket:

- You have all the Racket primitives for arithmetic and list manipulation.

- You have

lambdabut not higher-order functions. - You don't have

define.

To stop the Racket-1 interpreter and return to Racket, just evaluate an illegal

expression, such as ().

What Is an Interpreter?

In order to run a program on a computer, something in the computer must understand the intentions of the code, perform the necessary computations, and then return the results. This thing acts as a mediator between the programmer's ideas and the hardware that computes them. One such mediator is an interpreter.

racket is an interpreter for Racket. It translates Racket source code into instructions

that the computer, then tells the computer to execute them.

It has the ability to read input and display output.

Racket-1 is also an interpreter. It works for a purely functional subset of Racket. The fact that Racket-1 is written in Racket is interesting but unimportant. We could also write Racket-1 in another language, like Python, but what really matters to us as users is what the interpreter does, not what its source code looks like.

We'll talk more about interpreters in just a few lessons. For now, let's discuss how Racket-1 works.

How Does Racket-1 Work?

racket-1

racket-1 follows these rules:

To evaluate a combination:

- Evaluate the subexpressions of the combination

- Apply the procedure that is the value of the leftmost subexpression (the operator) to the arguments that are the values of the other subexpressions (the operands). To apply a compound procedure to arguments, evaluate the body of the procedure with each formal parameter replaced by the corresponding argument.

Example:

Racket> ((lambda (x) (* x x)) (- 2 (* 4 3)))

100

What happens here? Given the rules, walk through the evaluation by hand.

Read-Eval-Print Loop

An interpreter needs a loop that allows it to do all the things it does. Every

time you type a command, racket-1 parses and executes your input, returns the

output, and then waits for another command. This is called a Read-Eval-Print

loop (REPL).

Here is all of racket-1:

(define (racket-1)

(newline)

(display "Racket-1: ")

(flush-output)

(print (eval-1 (read)))

(newline)

(racket-1)

)

The first three lines simply print the prompt "Racket-1: ". The fourth line is the important one. Here, input is read, parsed and sent to eval-1 to be evaluated. After eval-1 takes care of executing the code, its result is printed. Finally, racket-1 calls itself to restart the process, to display another "Racket-1: " and take another command.

Eval-1

Eval-1 is in charge of returning the result of whatever computation it was

passed as exp. It is composed of a cond, with a clause for everything it can

interpret and compute. Note that it is in Eval-1 where special forms are

caught and handled.

(define (eval-1 exp)

(cond ((constant? exp) exp)

((symbol? exp) (eval exp)) ; use underlying Racket's EVAL

((quote-exp? exp) (cadr exp))

((if-exp? exp)

(if (eval-1 (cadr exp))

(eval-1 (caddr exp))

(eval-1 (cadddr exp))))

((lambda-exp? exp) exp)

((pair? exp) (apply-1 (eval-1 (car exp)) ; eval the operator

(map eval-1 (cdr exp))))

(else (error "bad expr: " exp))))

Apply-1

Apply-1 is called by eval-1 when it is time to apply a procedure to its

arguments. Apply-1 takes care of two cases:

- racket-1 primatives. In this context, a primative is a non-user-defined procedures. All Racket procedures are Racket-1 primatives.

- Lambda functions, or user defined procedures.

(define (apply-1 proc args)

(cond [(procedure? proc) ; use underlying Racket's APPLY

(apply proc args)]

[(lambda-exp? proc)

(eval-1 (substitute (caddr proc) ; the body

(cadr proc) ; the formal parameters

args ; the actual arguments

'()))] ; bound-vars

[else (error "bad proc: " proc)]))

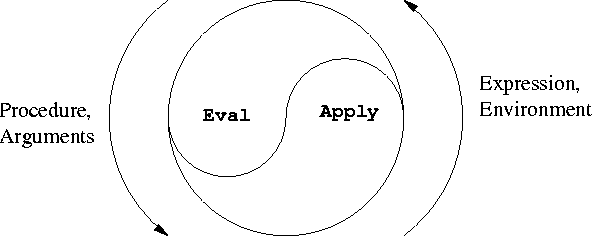

Mutual Recursion (in racket-1)

Practice with Racket-1

Okay, so even though you just finished staring at the code, you probably don't completely understand all of it yet. Let's go through a few exercises to better acquaint you with the program.

Manually trace through (in detail) how racket-1 handles the following procedure call:

((lambda (x) (+ x 3)) 5)

In particular, walk through all of the functions that racket-1 must call to evaluate this expression.

Try inventing higher-order procedures; since you don't have define you'll have to use the Y-combinator trick, like this:

Racket-1: ((lambda (f n) ; this lambda is defining MAP ((lambda (map) (map map f n)) (lambda (map f n) (if (null? n) '() (cons (f (car n)) (map map f (cdr n))) )) )) ;end of lambda defining MAP first ; the argument f for MAP '(the rain in spain)) ; the argument n for MAP (t r i s)Since all the Racket primitives are automatically available in racket-1, you might think you could use Racket's primitive map function. Try these examples:

Racket-1: (map first '(the rain in spain)) Racket-1: (map (lambda (x) (first x)) '(the rain in spain))

Explain the results.

- Modify the interpreter to add the

andspecial form. Test your work. Be sure that as soon as a false value is computed, yourandreturns#fwithout evaluating any further arguments.