Representing Sets

Intro to Sets

We have seen how we can use lists or trees to introduce hierarchy to our structure. Sometimes we don't care about a structure's hierarchy; we only need to know if a certain datum is in the structure. One useful structure for this is a set - a collection of unique data. In other words, sets will never contain two of the same element. For example, {cats dogs bears squirrels cats} is not a set because "cats" appear twice. In contrast, {cats dogs bears squirrels} is a set.

For this lesson, we will use lists to represent a Set ADT. This means we can create Sets using list and select from sets using car and cdr. The empty set will be represented by an empty list, null. Looking forward, here are some functions that we will define for the Set ADT:

element-of-set?checks if a certain data is in a setadjoin-setadds a new data to a set.intersection-setgiven two sets, returns a new set which contains only elements that are in both sets

element-of-set?

element-of-set? takes in two arguments, an element x and a set, and returns #t if x is in set, #f otherwise:

(define (element-of-set? x set)

(cond ((null? set) #f)

((equal? x (car set)) #t)

(else (element-of-set? x (cdr set)))))

This code is similar to memq. We used equal? because the member of a set

can be a number, symbol, or anything else.

Assume that set1 and set2 both have a length of n.

What is the running time of the function call below?

(element-of-set? (car set1) set2)

adjoin-set

Let's move on to adjoin-set! This function again takes in an element x and a set. If x is a member of set (we can check using our element-of-set? function), do nothing. Otherwise, add x to set:

(define (adjoin-set x set)

(if (element-of-set? x set)

set

(cons x set)))

intersection-set

intersection-set is a bit more challenging. Given two sets, set1 and set2, we need to find its intersection. We'll have to do this recursively. Let's separate this problem into cases:

- If either set is empty, return

null. - Check if

(car set1)is inset2.- If so, include that element in our answer and recursively call

intersection-seton(cdr set1)andset2. - If it is not in

set2, recursively callintersection-seton(cdr set1)andset2.

- If so, include that element in our answer and recursively call

Here is the code for intersection-set:

(define (intersection-set set1 set2)

(cond ((or (null? set1) (null? set2)) '())

((element-of-set? (car set1) set2)

(cons (car set1)

(intersection-set (cdr set1) set2)))

(else (intersection-set (cdr set1) set2))))

Assume that set1 and set2 both have a length of n.

What is the running time of the function call below?

(intersection-set set1 set2)

Set as an Ordered List

You might have noticed that our previous implementation of the Set ADT is

relatively slow. Finding the intersection of two sets could have a quadratic run time relative to their size. If a set is rather large, this implementation would be very slow. But don't worry, we can speed things up by instead using ordered sets, where data must be stored in increasing order. e.g., (1 3 4) is an ordered set, whereas (1 5 3 4) is not.

Similar to how alphabetizing names will make a roster easier to search through, using ordered lists to represent sets will allow searching and manipulating them to be substantially faster.

element-of-set?

One advantage of an ordered list is that we don't always have to explore the entire set to find a certain element. Let's make the necessary changes to element-of-set? so that it takes advantage of the ordered property.

element-of-set? still takes in two arguments, an element x and a set. Since we know that the elements of set are ordered, that means all we need to do is scan the set from left to right.

- If

(car set)is equal tox, then we stop and return#t. - Otherwise, if

(car set)is greater thanx, then we know that all other elements in the set will be greater thanx, and we can stop here and return#f. - Else, if

(car set)is less thanx, we'll have to move on to the next element insetand repeat.

This means that, if we're lucky and x is less than or equal to the first element of set, we can automatically return #f or #t without even looking at the rest of set!

Our code for element-of-set? will then be as follows:

(define (element-of-set? x set)

(cond ((null? set) false)

((= x (car set)) true)

((< x (car set)) false)

(else (element-of-set? x (cdr set)))))

Note: We make the assumption that all the elements in our set are numbers. If this is not the case, the above code will error.

Assume that set1 and set2 are ordered lists and both have a length of n.

What is the running time of the function call below?

(element-of-set? (car set1) set2)

intersection-set

Our previous implementation of intersection-set with unordered lists compared each element of one set to every element of the other set, giving it a total run time of Θ(n^2). In order to speed up this function using ordered lists, let's use a different approach to implement this function. We can split intersection-set into the base case (same as before):

- If either set is empty, return

null

and the following recursive cases:

(= (car set1) (car set2)): Since they share the same element, we include this element in our answer, remove this element from both sets, and check the rest by calling(intersection-set (cdr set1) (cdr set2)).(< (car set1) (car set2)): Since(car set2)is the smallest element inset2, we can conclude that(car set1)is smaller than all elements ofset2and thus cannot be inset2. We can continue searching with the next largest inset1by calling(intersection-set (cdr set1) set2).(> (car set1) (car set2): This is the mirror image of the case above. Since(car set1)is the smallest member inset1, we know that that(car set2)is smaller than all elements ofset1and thus cannot be inset1. We can continue searching with the next largest member inset2by calling(intersection-set set1 (cdr set2)).

The complete code for intersection-set can be written as follows:

(define (intersection-set set1 set2)

(if (or (null? set1) (null? set2))

'()

(let ((x1 (car set1)) (x2 (car set2)))

(cond ((= x1 x2)

(cons x1

(intersection-set (cdr set1)

(cdr set2))))

((< x1 x2)

(intersection-set (cdr set1) set2))

((< x2 x1)

(intersection-set set1 (cdr set2)))))))

Assume that set1 and set2 are ordered lists and both have a length of n.

What is the running time of the function call below?

(intersection-set set1 set2)

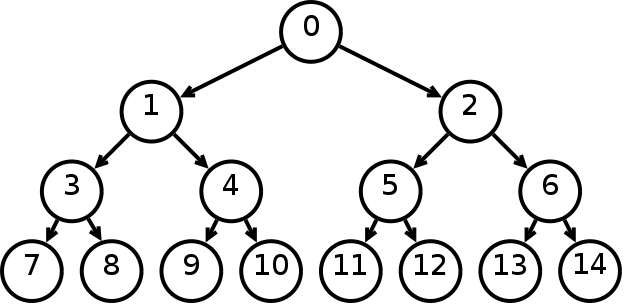

Set as Binary Tree

"I want to go faster"

In the need for speed, we must break free of the chains of lists that bind us to linearity. In other words, if we want our Set ADT to work even faster, we will have to use a different data structure than lists. How about using a tree?

A binary tree is just like the Tree we described earlier in this lesson, except for one important property: each node of a binary tree can have at most two branches.

Using binary trees to represent sets is simple and intuitive. The entry (analogous to datum) of each node in a binary tree will be an element of a set. Each node will also have a left branch and a right branch; the left or right branch of a node can be empty. If both branches are empty, that node is a leaf. This data structure must follow one rule: The left branch of a node must point to a subtree with entries smaller than the entry node. The right branch must point to a subtree with entries larger than the entry node. In other words, all values to the left of a node must be smaller than the node, and all values to the right of a node must be larger than the node.

This rule introduces logarithmic runtime into the picture. Walk yourself through finding 11 in the leftmost tree above. We start at the root of the tree and notice that 11 is greater than 7, and so we travel down the right branch. 11 is greater than 9, and so we again go down the right branch. We have found 11 in the tree and can return #t.

Okay, now let's try to prove this logarithmic run time. If you don't want to see the entire proof, you can skip ahead to the TL;DR section.

Take a look at the worst-case tree below:

- The maximum number of nodes you will have to explore, ever, is equal to the depth of the tree, or how many levels the tree has. (The depth at the root is 1.) Take a moment to confirm this.

- We are given that the set has size

n, and so there arennodes in the tree. - At depth 1, there is 1

(2^1 - 1)node. At depth 2, there are 3(2^2 - 1)total nodes. At depth 3, there are 7(2^3 - 1)total nodes, ...and finally, at depthd, there are(2^d - 1)total nodes.

We learned in Lesson 3 that in asymptotic analysis, we can ignore constants, so let's just say that at depth d, there are 2^d total nodes. This means that any tree with depth d will have 2^d nodes in the tree.

We know that there are n total nodes in the tree. That means 2^d = n.

After doing some cool algebra magic, we get d = log(n).

Remember how we said that the maximum number of nodes we'll ever explore is equal to the depth of the tree? This means the run time for finding a node in a binary tree is Θ(d) = Θ(logn). And thus, we have proved the logarithmic run time of using a binary tree to represent sets. Phew!

TL;DR: The ordering of the binary tree structure allows us to ignore half of the tree after every comparison. This means that the maximum number of nodes we'll ever have to explore equals the depth of the tree. This leads us to a running time of Θ(log n). e.g., in a tree with 8 nodes, we just need 3 comparisons max until we reach any leaf. In a tree with 16 nodes (double the previous one), we just need 4 comparisons (just 1 more comparison!) until we can reach any leaf.

Implementing a Binary Tree

One way to implement a binary tree is by using a list where the first item is the element, the second item is the left subtree and the third item is the right subtree.

(define (entry tree) (car tree))

(define (left-branch tree) (cadr tree))

(define (right-branch tree) (caddr tree))

(define (make-tree entry left right)

(list entry left right))

element-of-set?

We can formalize our algorithm for finding if an element is in a set with the following code:

(define (element-of-set? x set)

(cond ((null? set) false)

((= x (entry set)) true)

((< x (entry set))

(element-of-set? x (left-branch set)))

((> x (entry set))

(element-of-set? x (right-branch set)))))

Super simple stuff.

adjoin-set

How do you add an element to a binary tree? Since you need to decide whether to add x in the leaf of the left subtree or right subtree, let's follow the same algorithm element-of-set? above.

- If the tree is empty, make a tree with node entry

xand empty left and right branches. - If x is equal to the node of the tree, return the tree. (This means

xis already in the tree and no changes need to be made.) - If x is less than the node of the tree, go to the left subtree.

- If x is larger than the node of the tree, go to the right subtree.

Here's the formal algorithm for adjoin-set:

(define (adjoin-set x set)

(cond ((null? set) (make-tree x '() '()))

((= x (entry set)) set)

((< x (entry set))

(make-tree (entry set)

(adjoin-set x (left-branch set))

(right-branch set)))

((> x (entry set))

(make-tree (entry set)

(left-branch set)

(adjoin-set x (right-branch set))))))

Unbalanced Tree

The image above is the result of adding the elements 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, in that order, to an empty tree. (Make sure you try this out with pen and paper to see that this is the case). We say that this tree is unbalanced because one side of the tree has way more elements than the other.

In the unbalanced tree above, what is the running time of finding an element (e.g., 7)? n is the the number of nodes in the tree, where n = 7.

Challenge: Can you think of an ordering to add the same numbers so that we create a balanced tree?

Different Types of Trees

Previously, we saw how nodes in a tree can have an arbitary number of

children. These types of trees are sometimes called N-way trees. For N-way

trees, we store the children of the tree as a forest, or a list of trees. We

retrieve this forest through the selector (children <tree>).

In the previous section, we saw a more specific type of tree, binary trees.

Each node in this tree has at most 2 children. They can be accessed with

(left-branch <tree>) and(right-branch <tree>). The constructor for a

binary tree is also different than the constructor for an N-way tree.

When you are working with trees, find out what kind of tree you are working with and notice the constructors and selectors that the question provide. The constructors and selectors for a binary tree would not work at all on an N-way tree!

Takeaways

A set is a particular data structure where each element appears only once. There are multiple ways to represent Sets (as with basically all data structures). The choice of representation affects the run time of different functions.